The theme of World IA Day 2016 was: “Information Everywhere, Architects Everywhere.” I got an email message that described the theme further. It said, “Because of the ubiquitous nature of information, information architecture is not just practiced by specialists. Instead, we see information being architected by people holding all sorts of titles, coming from all walks of life.”

This got me thinking about what makes an Information Architect. Everyone does information architecting—you don’t even need a computer to do that! Far fewer people do Information Architecture. I’d argue that there is a toolkit difference, a mentality difference, a difference in the way of approaching the world.

When I say information architect, I don’t mean it like a job title. Your job title may be UX Designer or Event Planner or Administrator or Product Owner—but the way you approach your world might be as an Information Architect. I mean “Information Architect” in the way people mean “Engineer.” When people say “Engineer,” everyone has a stereotype of what that is, and they think they understand the value of an Engineer. Dilbert is a great example of that stereotype. Engineer is an identity, a way of approaching the world, an affinity your friends and neighbors won’t let you forget.

Last year at about this time of year, my husband and I were sitting in the ultrasound room at the hospital excited to see our baby for the first time. Then the technician said, “There are two in here! You’re having twins!” I was speechless, lost for words like all the air went out of the room. But my husband knew just how he felt. He said, “Well, that’s efficient!” And every time I tell that story, perfect strangers will say, “He must be an engineer!” And he is!

At least, that is what his degree is in. He doesn’t describe himself as an engineer. It is not his job title. His day-to-day activities aren’t what you or I would consider engineering. Yet anyone who met him would guess he is an Engineer. There is something we associate with an approach that leads us to think of someone as an Engineer.

What exactly that is would be difficult to describe, but I think you could summarize like this: an Engineer approaches the world in a certain way. They have a certain mindset. And that mindset is highly valued in our society. Of course you need an Engineer on the project! No question.

We here at World IA Day events in 2016 are in a new-ish field that isn’t well understood by the world. It would be a relief to have our own stereotype—for people to say, “He must be an IA!” What might that definition, that approach that defines us, look like? What IS the IA value proposition?

What is the Information Architect’s Approach?

We have to sell our skill set all the time. We are more than our deliverables. We have to sell our process. We have to defend our ability to do proper discovery—stakeholder interviews, content audits, user interviews, modeling. Many of you in this room work at companies where your tasks are rigidly defined and your time is closely watched.

I’ve given a few talks on the value of conceptual modeling—of working out the problem space thoroughly before designing solutions—and after each talk, people tell me how difficult it is to make the case for conceptual work in their workplaces. The truth is, the activities that lead to deeper understanding and better solutions are also more difficult to explain—and more difficult to sell—than other more brass tacks activities like wireframes and specifications.

Many of you in this room are students at the start of your careers. You have a lot of knowledge gained through your courses, and that can make you feel like you should know the right answers. You hear questions like: What do you mean defining the problem? Why can’t you just build it? How many solutions could there possibly be? Why don’t you just know the right answer? It’s just a simple website, or app, or console, or on and on and on.

IA isn’t about having the right answers; it’s about having the right approach that gets you to the right answers, and I hope this talk helps you defend the right to have that approach.

We are the ones who care about figuring out why we would build something before building it. We are the gatekeepers that hold off the solutions—the How—until we know the What and Who and Why. Defending and explaining the importance of holding off the construction process can be really difficult.

Pace Layers

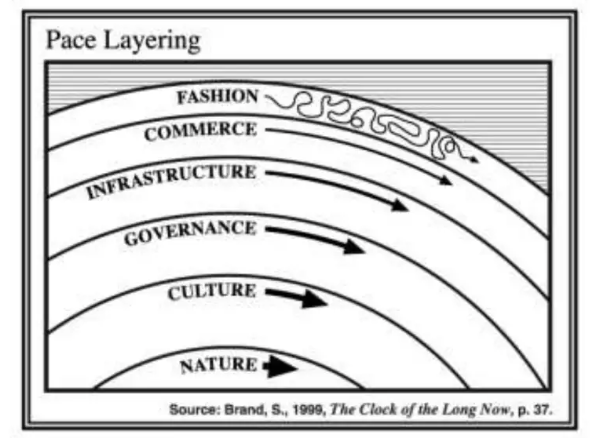

Many of you are probably all familiar with pace layers. It is a way of expressing rate of change. Everything changes, but at very different speeds. In Stewart Brand’s diagram, we see nature at the center. Nature changes slowly. Culture changes a little faster. Fashion, on the outermost circle, changes quite quickly.

What would an IA’s pace layers look like? I think the desire to make the complex clear is our center circle. Clarity wins. For me, that means clarity of meaning. We are building digital places—places people go to and interact with. The only building material we have is information, and the meaning of that information changes that building material. You can build a wall out of bricks, but if suddenly the meaning shifts and one of those bricks is a pony, well, that’s no longer a very good wall!

Defining Meaning

Stewart Brand’s pace layers next to information architecture’s pace layers.

Here at World IA Day 2016, there is a feeling of togetherness, comradery—that we all agree that making clear things—good things—matters. That’s our core: Clarity Wins. What I want to discuss is the next layer: Approach-Toolkit / Mentality / Orientation. The difference between us and the Engineer or the physical architect is that our approach doesn’t result in something physical. If there is a bathroom in the garage and none in the house, everyone knows something is wrong! And everyone can see why an architect would model before building: building a house costs a lot of money, takes physical resources and space! I would argue that our Approach is even more crucial because we are dealing with the meaning, defining the meaning of things. That meaning changes when it is related to other parts of the world. There are physics to meaning and structure, and it is very, very possible to do it wrong—to mess up. A door is always a door to an architect; a door is not always a door to us. We can spend an hour with a room full of stakeholder making sure we all mean the same thing when we say the word door, and that time would be very well spent! A project has spun off course many a time because no one had the IA approach of exposing the parts, making sure we know what we mean when we say what we say, determining a system, ensuring the integrity of meaning is still intact. But this skill we have, this Approach, is very difficult to talk about. So let’s try.

An Example of Using IA Pace Layers

Imagine someone shows you a webpage or wireframe (this picture is intentionally vague). They ask, “What do you think?” There are plenty of things you could say about the Application—how it adheres to and differs from the norm. To discuss the Tools, you could recognize a standard layout and know they used WordPress or an Axure library. There are plenty of things you could say about the use of Best Practices such as, “Way to put a picture of ‘people like me’ front and center!”

When it comes to Approach you can’t say anything. You don’t know the answers to the What questions: What are the parts of your business? Purpose? Mission? Who are your users? This is what I mean by Approach. Sandwiched between our ideals about clarity and the practicality of best practices, What is our lens on life that encourages us to seek out answers to all the questions and compels us to sort them to reveal their patterns.

Exposing, Determining, and Deciding Together

Let’s talk more about this Approach pace layer. There are three main chunks to this Approach. It’s not a linear thing, but a cyclical process: exposing the parts, asking the stakeholders, “Are these the right parts? All the parts? What else?” Then determining the system those parts suggest or form. Working out that system often results in discovering more parts. And discussing that system with the stakeholders yields further and further insights. Deciding together is the binding element of all the activities that occur within the approach layer. All of this is in service to defining meaning, which is in service of clarity.

To dig into these parts of the IA Approach, I’d like to talk about it at a high level by focusing on a non-digital project: fort building! We all have experiences with forts. We’ve played in them or even built them. There are many types of forts from cardboard to community playgrounds. Today let’s focus on the age-old backyard fort.

Building a Backyard Fort—An Example

The project of building a backyard fort has a lot of similarities to any digital project. There are users to consider, stakeholders to consult, tools to utilize, time constraints to adhere to, risks to mitigate, and budget constraints.

Exposing the Parts

How do you find the parts? Mostly by asking the right questions. That can take the form of literally asking questions in an interview, or by investigating questions on a website, or by performing a content audit, etc. In our example project, you are building a fort. Here are some parts exposed by interviewing your child and your spouse. They, of course, wouldn’t literally tell you these parts. They would talk on and on about how they envision the fort looking, and what they want to be able to do with it. There would be a lot of HOW, like: “I want a slide that looks like a dragon I can slide down, but it never gets hot like the one at Steve’s house.” Then it is your job, with your IA approach, to boil that down to a slide.

Determining the System

Once the parts are exposed, you can all talk about the same things with the same words. This is an opportunity to ask more questions—the biggest one being: is there something missing? But also, this creates opportunities to get the right nuance. You can clarify further: “Tell me what swing means to you?”

Ask, ask, and ask some more.

In order to clarify the meaning, we often start conversations with, “I’m going to be dumb now in service to being clear—it’s really important that we nail down what we mean when we say what we say.” After this process of refining the meaning of the words in our backyard fort system, Look becomes Survey and Cheap becomes Affordable.

Group and Arrange the Parts

Once you have the parts, you can group and arrange them.

Here we see the parts from our fort interviews placed into one sort of system. It’s showing the relative importance of the parts and the major groupings they fall into. The dragon slide you heard your child describe was overshadowed by the numerous times they mentioned climbing. You spouse didn’t have any overlapping parts with your child, so you can split the goals into two big, clear chunk: Play and Safety.

Once the system is determined you can discuss the relationship between those parts and the new meaning it creates. You might also make a quick sketch of how these action goals relate to each other in sequence. Gaining some heighth is necessary to get to survey and hang and slide – so it’s natural to have climb lead to those parts. This particular action of determining the system would take you seconds, and would get your brain thinking in new and advantageous ways.

A Model for Clarity

Here is a system of parts from a past project. Clearly there are hundreds of parts that fall into three main categories. There are further categories exposed through color-coding. Each part takes on additional meaning through its connection with other parts, forming a huge system that represents the client’s world. This might look like a tremendous mess, but it’s actually representing tremendous clarity. Our project ended with this model as the main deliverable and it lived on the client’s wall for years. They wrote to us to tell us how often they referenced it when making implementation decisions or explaining the ecosystem to a new employee or determining where a new part fits into their existing world. This is not an ER diagram; it’s not about implementation. It is conceptual, much like the fort diagram. There are systems at play—almost like physics. You can do it wrong. You can break it’s meaning. Exposing it is critical!

Deciding Together

Deciding together happens throughout the project. Every stage of the process was shown to our clients as the work progressed. This ensures alignment and also shares the ownership of the decisions so that after we, as consultants, leave the project the stakeholders own their solutions. They know why decisions were made and why the structure is the way it is – making it more likely that the clarity we achieved will endure.

Meaning is Negotiated

“Each category valorizes some point of view and silences another.”

A word of caution: When we create these systems it’s a huge responsibility. Meaning is negotiated, and we have to do it together. What are the criteria for making, the criteria for what good is, and the criteria that determines that something works? These criteria are not an engineering problem.

Managing the Tensions

When there are tensions, a great way of discussing them is through intension models. In our fort example there is discord between hide and surveil. You can’t see a hidden child, but hiding is part of playing. So where is the balance? You can’t be all things to all people. So we talk about the conflicts.

Here is an example from a digital project showing real results. The stakeholders anonymously answered the question, and then the nine answers were discussed. The group ultimately landed on medium global focus. Directionality on these tension points is required for a project to move forward. You can’t be all things to all people.

At the core of our IA Pace Layers we have Clarity. With our IA Approach, we respect the seeking of clarity. Once we’ve exposed the parts, determined the system, and decided together we layer on best practices, tools, and application—all the while respecting the pace layers that came before. This results in great products!

Great Final Products

Maybe our final product would look like this. You want to be able to watch your child, so there is a railing with open bars. There is also a little panel behind which he can hide and peek out the little holes. The stakeholder knows what they are getting because it all maps back to the parts that were exposed and the systems that were defined that were all decided on together. Nobody asks why there are so many ways to climb, because climbing was determined to be important.

Negotiating Meaning—An Example with Childcare

Remember my ultrasound story? My husband was being a stereotypical engineer in his response, “that’s efficient!” When I recovered, I was a stereotypical IA! I started thinking about the ramifications of having two babies. Being very budget conscious, my head first went to childcare. We were discussing it before we left the hospital parking garage.

First we laid out the parts: We both planned to continue working, and we had a budget for what we planned to spend on daycare. I actually had it all mapped out for Kid One in 2015 and Kid Two in 2017 and projected costs all the way through graduation from college. I’m a planner. I’m an IA. Well, now I was having twins. So the parts of what I was considering about childcare weren’t changed: cost, schedule etc. But their meanings were certainly changed. Schedule now meant getting two babies ready in the morning. Travel now meant two car seats and two hats and two coats.

Our priorities on these parts also didn’t change when we found out we were having twins. But due to Cost being one of our biggest circles, daycare was out of the question. Daycare costs double for double the babies. A nanny coming to your home costs only marginally more.

This shift from daycare to nanny, though, changes the meanings of these parts! Travel no longer means my travel with the boys—now it means my nanny’s travel. Does she have a reliable car that can get to our house in a snowstorm?

Schedule is no longer 8-5 and we can’t be late—it’s more of a give and take where we respect each other’s time and have to flex to each other’s schedule. A daycare worker having to go to the dentist wouldn’t affect my schedule—but my nanny’s dentist appointment changes my whole week! We went with a nanny, and she is great.

I hope all of this helps you to be more confident in your IA value proposition. You are doing amazing things in this world—determining meaning in service to clarity—making the world be good.

There is a Need for More Information Architects

If I may add one additional point: We need to encourage and develop the IA tendencies in those around us—to grow those who do architect-ing into architects. There is no need to be competitive about this type or work. We are not making paper mache angels—the market for IA work is limitless. I strongly believe that if we become good at explaining the core of IA and good at recognizing that core in others, if we got good at encouraging and complementing those who are also trying to make the complex clear, if we do that, there is no limit the number of IA projects in the world.

Complex Problems Need More Complex Solutions

Often when people don’t see the value of IA, it’s because they view the project as simple—like building a snow fort. They think you are suggesting you need an architect to build one. Everyone understands you need a professional to build a fort at a business like a children’s museum. Business forts have more requirements and higher risk (people sue!)

To build a snow fort the only material you need is snow. The audience is the person making it. No formal, outside approvals are required. The risks are limited. Clean up takes care of itself when the weather warms, and pretty much anyone is capable of making one.

A fort within a business requires materials such as wood, nails, steal beams, steal cables, etc. Qualified professional companies bring in skilled tradespeople with tools. The audience is the public of all ages. Approval is needed from stakeholders within the business and from inspectors who certify that certain legal standards are met. The potential risks are huge.

The projects that we’re working on are more like the business fort than the snow fort.

Slide Deck

Here’s the link to the YouTube video to watch the entire presentation.